As explained in the previous post it is not the size of the government debt that has a direct impact on the public finances; it is the interest cost it generates (though the size is obviously a big factor in that)

What was in play with yesterday’s restructuring was a €25 billion Promissory Note debt. It was a €25 billion debt on Wednesday, it is a €25 billion debt today and it will be a €25 billion debt in 2053. But because of inflation not all €25 billions are created equally.

Anyway, the debt in question generates two interest costs for the State:

- The interest on the central bank funding which carries an interest rate equals to the ECB’s main refinancing rate.

- The interest on the borrowings used to pay down the central bank liquidity.

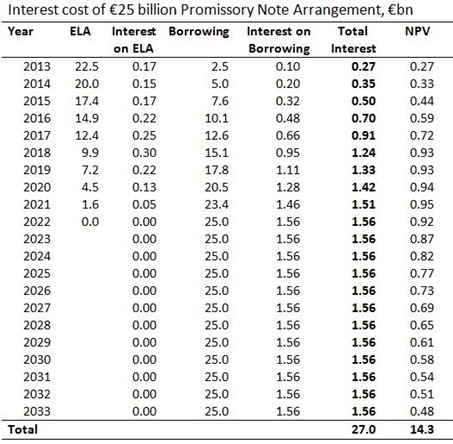

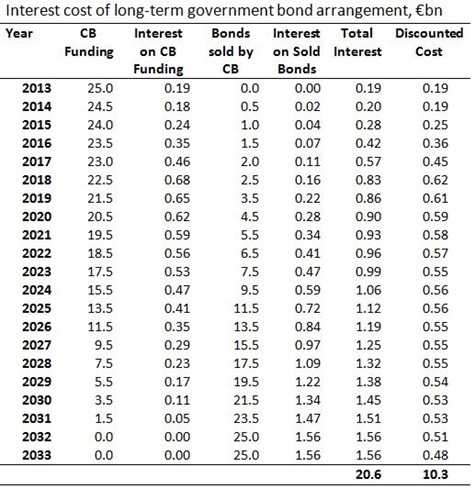

Here are two tables that showing some hypothetical the interest costs of the old Promissory Note and new Long-Term Government Bond arrangements until 2033.

These are only hypothetical scenarios designed to gauge the relative difference in the cost of each approach rather than a definitive estimate of the cost of each. There are a number of simplifying assumptions made.

- The ECB interest rate is expected to rise from 0.75% to 3.00% over the next six years and stay at 3.00% thereafter.

- The ‘margin’ of Irish government borrowing over the ECB rate is assumed to be constant 3.25%.

- All interest is paid from current revenue.

- Borrowings are only made to fund capital payments. This only impacts the Promissory Note arrangement and from each €3.1 billion annual payment the Central Bank profit is subtracted as it is returned to the Exchequer and also the external interest cost of the ELA as it is assumed that is paid from current revenue. This keeps the borrowing at €25 billion in both cases so we can assess the interest cost.

- The discount rate used is 6%.

As we are looking for relative differences the assumptions are not hugely significant as both scenarios are played out under the same set of assumptions.

First the Promissory Notes:

And the new Long-Term Bond arrangement:

The interest mix of both changes. In the first case it is because the Promissory Notes/ELA costing the ECB rate is paid off with new government borrowings at the “market rate”, while in the second case the Central Bank funding at the ECB rate is reduced through the Central Bank selling the bonds it holds thereby making the interest payable to a third party. By 2034 both arrangements are identical in this setting - a debt of €25 billion with an annual interest cost of €1.56 billion (assumed interest rate by then is 6.25%) - as all the Central Bank funding is repaid

So what do we find in? In nominal terms the interest costs are

- Promissory Notes: €27.0 billion

- Long-Term Bonds: €20.6 billion

Getting the present value of the interest payments gives:

- Promissory Notes: €14.3 billion

- Long-Term Bonds: €10.3 billion

The interest cost under the new arrangement is around 30% lower. This is a gain to the State of the new change which arises from having access to borrowings at the lower ECB rate for longer. It increases from c.7 years to c.15 years.

The are other gains from the new arrangement. The above just reflects the interest cost of each arrangement. The accounting treatment of the Promissory Notes meant they had a very large impact on the deficits over the coming years. That has now been reduced. Also the new arrangement means that the debt doesn’t have to be rolled-over until the first of the new bonds matures in 2038 significantly reducing the medium term funding needs of the State.

The is little doubt that the new arrangement is anything other than a gain for the State. And unless your expectations were incredibly unrealistic (or more accurately based on fantasy), yesterday’s announcements were pretty much as good as could have been hoped for given the institutional constraints faced.

Tweet

Séamus

ReplyDeleteThat is an excellent piece of work. I had been thinking about trying to compare the NPV of both deals to quantify the benefit of yesterday's deal.

€4 billion seems about right to me.

A couple of questions -

"The ‘margin’ of Irish government borrowing over the ECB rate is assumed to be constant 3.25%."

Is this a reasonable assumption? Will that margin not reduce over time as we get our affairs in order?

Why choose a discount rate of 6%? I would probably have used the current cost of government funding which is around 4%.

I presume you can make a case for either set of assumptions.

If you reduced the margin from 3.25% to 2% and reduced the discount rate to 4%, what would the resultant NPVs be?

Hi Brendan,

DeleteI wouldn't hang my hat on the nominal NPV difference; I think the relative reduction of 30% is the better measure.

The assumptions can be questions but as the focus is on the relative difference they are not hugely significant. Different assumptions would change the €4 billion figure but the 30% relative difference would likely remain.

Séamus,

ReplyDeleteExcellent post as always. Do you understand what has happened to the IBRC government bond that was being held as security in repo agreement with Bank of Ireland?

In theory the liquidation of IBRC should have meant that the Bank of Ireland will not get repaid the €3.1 billion it provided IBRC in a repurchase agreement in June of 2012. However, in the document published to the markets concerning this transaction on the 30th of May 2012, the bank stated that a guarantee from the Minister for Finance of Ireland existed for this transaction.

“All of IBRC’s payment obligations to the Bank with respect to the Transaction will be covered by a guarantee from the Minister for Finance of Ireland of IBRC’s exposures for transactions of this nature.”

http://www.bankofireland.com/fs/doc/wysiwyg/proposed-securities-repurchase-transaction-and-notice-of-egc.pdf

Section 290 of the 1963 of the Companies Act in Ireland allows the liquidator to seek to disclaim onerous property. It is clear that this repurchase agreement would be seen as onerous property as the consideration for the agreement is €3.1 billion cash that the liquidator of IBRC does not have.

“290.—(1) Subject to subsections (2) and (5), where any part of the property of a company which is being wound up consists of land of any tenure burdened with onerous covenants, of shares or stock in companies, of unprofitable contracts, or of any other property which is unsalable or not readily saleable by reason of its binding the possessor thereof to the performance of any onerous act or to the payment of any sum of money, the liquidator of the company, notwithstanding that he has endeavoured to sell or has taken possession of the property or exercised any act of ownership in relation thereto, may, with the leave of the court and subject to the provisions of this section, by writing signed by him, at any time within 12 months after the commencement of the winding up or such extended period as may be allowed by the court, disclaim the property.”

http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/1963/en/act/pub/0033/sec0290.html#sec290

Without detail, the Irish Prime Minister (Taoiseach) announced in his speech that the Central Bank of Ireland has now taken ownership of the €3.1 billion government bond which the Bank of Ireland acquired as a security for repurchase agreement with IBRC.

“In addition, the liquidation of the IBRC has caused the Central Bank to take ownership of the €3.4 billion bond used to settle the promissory note last March.”

http://www.merrionstreet.ie/index.php/2013/02/taoiseachs-speech-on-agreement-with-the-ecb-on-the-promissory-notes/?cat=11

Presumably the Central Bank of Ireland’s economic ownership of the Irish government bond that was issued to IBRC is because at the time of liquidation, Bank of Ireland had repo’d this government bond in the Central Bank of Ireland. It’s not clear whether this means that Bank of Ireland’s cash reserves which were being boosted through repo’ing the government bond have essentially been permanently transferred to Bank of Ireland by the Central Bank of Ireland given the liquidation of IBRC or whether the Central Bank of Ireland is just holding the bond as security for the defaulted IBRC.

The Taoiseach used the word “owner” while Department of Finance talks about “hold”.

If the Central Bank of Ireland is not the economic owner of the bond, the Bank of Ireland has a ministerial guarantee to honour the cash repayment terms which would in effect mean that the €3.1 billion the exchequer did not spend in 2012 in consideration for the promissory note, would now be spent to honour the ministerial guarantee. Although this isn’t very clear from the Department of Finance’s official presentations.

How did Bank of Ireland get their cash back and who paid for it?

Hi John,

DeleteThis was mentioned in passing in a couple of briefing's yesterday but in the rush to try and assimilate the broader details I missed on some finer points such as this. I am hoping to find a recording of the DoF briefing somewhere but to no avail so far.

BOI will get their money back. There are some "liquidation costs" included for 2013. These include a claim of €1 billion under the ELG. I assume this is related to the BOI repo. It is likely that the set of transactions with NAMA/CBoI leaves a shortfall to cover the repayment, hence the ELG steps in. This is not an additional cost as the IBRC was going to have to meet the full cost of the repo anyway so it is just an accounting exercise.

Hi Séamus,

DeleteThanks, yeh I watched the briefing live and didnt hear sufficient detail on this.

So you think that additional NAMA bonds would be issued as consideration for IBRC liability to Bank of Ireland above the ELG downpayment and essential NAMA bonds would be given as consideration for something else other than the ELA debt.

Seems plausible, its just that IBRC shoudlnt have to meet the cost of the repo, it should be the ministerial guarantee honoring the repo as IBRC in liquidation and that repo agreement would be onerous property liquidator should disclaim rather than liability.

Curious anwyay, if I uncover any further detail, will post here.

Thanks,

John

Hi Séamus,

DeleteBelow is what Noonan said on the matter on Pat Kenny this morning.

http://www.rte.ie/radio1/today-with-pat-kenny/

“Then they decided to compensate us again on that because you remember last year when we didn’t pay the promissory note, we replaced it with an Irish government bond and that’s in possession now in the Bank of Ireland and we’d have to redeem that in June because they’re holding it for one year.

But what the bank did when they were pressing us to sell early, the also agreed to roll that in with the basket of bonds so the €25 billion of bonds would go up to over €28.5 billion because the interest rate on that was 5.4% and because the maturity is very short relative to the rest of the portfolio the governor will be able to sell slices of that to meet our requirements to sell up front so we didn’t lose anything off the main deal cause they kind of compensated us by allowing us to include the bond in possession of the Bank of Ireland in the overall portfolio.”

Part of the deal seems to have been that the bonds which will be held by the CBI have to be 'marketable' - that is, have to be sold off in the markets to become normal government financing, which makes sense from a 'no monetary financing' point of view. And while the CBI *must* sell some bonds, it can do so after looking at how the sale would impact the Irish banking sector - but it must sell bonds, and be seen to be selling bonds. From our perspective, such bond sales increase the real cost to the state of the bonds.

DeleteThe inclusion of the BOI bond in the package gives us €3.1bn of bond at an interest rate which is not very good - 5.4%. As far as I can see, the ability to sell slices of that, at what will probably be a lower interest rate, gives the CBI the ability to meet the need to be seen selling the bonds, while simultaneously *reducing* rather than increasing the real cost to the state.

If I'm right, that's a very nice sweetener.

Scofflaw, makes sense.

DeleteIf the Bank of Ireland government bond is sold at a lower interest rate to markets, presumably that means the Central Bank will make a profit on the sale that it can then return to exchequer?

Good sweetner.

Still don't understand how or who paid Bank of Ireland for the government bond yet however.

Seamus

ReplyDeleteYour calculation of the interest cost is very low in the first few years but yet the Dept of Finance figure show 800m in 2013 and rising to 950m in 2015. Why the difference?

Hi Anonymous,

DeleteIt's because they are different interest costs. The DoF figures are looking at the "savings" on the deficit. The Promissory Notes were charged at a rate of 8.2% on all deficits from 2013 on. The elimination of the Promissory Notes eliminated this cost from the deficit. This has now been replaced with the long-term bond which come at an interest rate of 3.3%. The gap between these two rates is the main reason for the interest cost reduction reported by the DoF.

However, this isn't a an actual saving as the interest on the Promissory Notes would have been paid to the IBRC, which although state-owned is counted outside the general government sector by Eurostat, while to start most of the interest on the new long-term bonds will be paid to the Central Bank which will recycle the profit it makes back to the Exchequer.

The figure I worked with above is the final cost of the debt, i.e. interest that leaves the broader government sector as it not paid to the IBRC or the CBoI. This comprises the interest the CBoI pays to the ECB for either allowing the ELA or allowing the CBoI to hold the bonds and second the interest on the borrowing used to repay the Central Bank liquidity. Initially the interest cost is mainly the Central Bank liquidity and as this is charged at the ECB MRO rate the interest bill is lower.

The numbers are different because it is apples and oranges.